Forming Places that Form Ideas: Creating Informal Learning Spaces

Learning can happen anywhere: from parking lots to classrooms to residence hall lobbies. The challenge is to plan these spaces so that they offer the opportunity for, but not dictate, a specific type of learning activity. Often in use and occupied on a 24/7 basis, undesignated and unscheduled spaces must be particularly resourceful.

“The space between” is how Shirley Dugdale and Phil Long describe informal learning spaces in higher education institutions. These are the places between classrooms and lecture halls, workspaces and meeting rooms, labs and seminars. *1 They are the places where students and faculty socialize, network, and study, where class discussions are continued and group projects are completed, and where impromptu encounters occur.

“Places where serendipity happens” is how Susan Whitmer of Herman Miller, Inc., defines them. *2 “The successful informal learning areas I’ve visited have a few key characteristics in common,” Whitmer explains. “Every element of the space is inviting. It has great lighting, both natural and controllable. A variety of furnishings that support group interaction, reflection, and idea exchange. Lots of whiteboards and display tools for sharing ideas. Electrical and wireless access for computers and mobile devices. The attraction of food and beverage is always a plus. Mainly, these are places that have been planned for unplanned, unscheduled, anytime learning.”

Informal learning spaces are increasingly part of the college campus. Rarely does Whitmer have a conversation with educators and interior designers that doesn’t include the component of informal learning. “The conversations tend to focus on the value of unplanned, impromptu meeting places. The scope of these spaces has expanded beyond collaboration. They’re more about providing places for student engagement and impromptu meetings.” *3

These places have transformed from small study break areas adjacent to libraries (often added as an afterthought with vending machines and a smattering of lounge seating) to full floors of multiuse, technology-rich, and service-oriented space with cafés, presentation and multimedia areas, organic design and vibrant colors, and, yes, lots of lounge seating—all built for providing social, interactive, and stimulating places in which informal learning occurs.

What We Know

People are attracted to environments that provide changing stimuli. Consider coffee shops, city parks, or public lobbies. They are filled with people doing all sorts of things: working, eating, visiting, or simply taking in the sights. This is nothing new. In the 5th century BC, Greek cities included an agora, the open space in the middle of the city or near the harbor that was a meeting ground for a variety of activities. The word itself refers to both the physical place and the gathering of people.

Perkins Library at Duke University, “is not unlike the ancient marketplace, or agora,” writes Duke’s Thomas Wall and Marilyn Lombardi. This informal learning space within the library “serves students and faculty as an inviting ‘third place’ and the center for student life.” *4 These types of places recognize how the human brain operates, according to Terry Hajduk, a learning environments specialist. “Our human hardware and software are wired to the social aspects of informal learning spaces.” *5

The culture of the times, however, has also influenced the changing campus environment and styles of learning. Our society is a social and highly interactive one. “Hanging out,” virtually and physically, is what Gen-X’ers, Net-Gen’ers and Neo-Millennials do. Social networking sites and text and instant messaging are a large part of peer interaction. So are places where physical interactions occur. But students don’t have the corner on social networking—virtual and other. It extends to university faculty and staff as well.

Students today also come to higher education with a greater sense of independence and ownership, says Whitmer. “Students want to own their learning. They expect a higher level of control over decisions such as when, where, and how they will study.” *6 Dugdale and Long describe the Net-Gen and Neo-Millennial students as experimenters and action-oriented people. They are highly visual, group focused, and media fluent. *7 The environments in which they spend their college years need to recognize and address these characteristics in their design.

Learning as a social activity is a phenomenon of more recent times. Robert Barr and John Tagg introduced the idea of a learning paradigm in the late 1990s. Their critique of an instructional model—the traditional paradigm—and its inability to foster engaged and life-long learning, is now acknowledged and accepted.

“We know more than ever before about how people learn, what inhibits learning, and different kinds of learning. The image of the college student sitting passively, taking notes, while the professor stands front and center disseminating information is being replaced with an image of students engaged in activity, in groups, moving around the space, leaving the space to work elsewhere, interacting with students or professors via technology, while the professor moves among them interacting, facilitating, fostering engaged learning,” writes Michael Harris and Roxanne Cullen in “Renovation as Innovation: Transforming a Campus Symbol and a Campus Culture.” *8

In Renata Caine’s Mind/Brain Learning Principles, she outlines the connections between brain function and learning. One of her twelve principles is that the brain/mind is social. People change in response to engagement with each other. *9 Environments that provide for a rich variety of engagements and experiences should provide, in turn, fodder for brain stimulation and learning.

Peer-to-peer engagement and group work are effective forms of learning. Problem solving, testing one’s ideas against another’s, and modeling/observing styles of learning are benefits of social learning. “Collaborative spaces,” says Whitmer, “foster creative thinking. To be creative and to form ideas, students need environments in which they feel relaxed and comfortable but also stimulated and engaged.”

Community and social space connects individuals with other people and with other activities. Students and teachers are involved in a mutual endeavor—learning—and connections that reinforce learning are important in creating a sense of belonging, writes Lori Gee of Herman Miller. *10

Any place on campus can be a learning space. Hallways, dorm rooms, classrooms—learning can happen anywhere. The informal learning landscape, state Dugdale and Long, is one that is moving from “location-centric to location-independent learning discourse.” *11

Gee explores this idea further: “Consider the potential of hallways and ‘pathways’ that provide unexpected spaces for group work, casual conversations, or hiding away for quiet work. Environments that are informal and relaxed will enhance creativity and spark connections.” Educator Barbara Prashing writes about the emergence of new ideas during social interactions. Places that support chance encounters or areas to linger after a class support such social interactions. *12

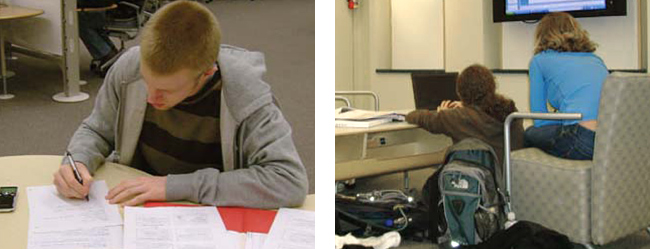

The flexible, adaptable spaces at Xavier University’s Learning Commons support both individual (left) and group (right) learning experiences. Herman Miller’s Resolve and Intersect portfolio products provide comfort and flexibility that enhance the experience.

Connecting visually lets people feel they are a part of something bigger. To see people engaged in learning can be energizing. Consider adjacent areas and how to connect formal and informal learning spaces, such as classrooms and lobbies. Corridors, too, become part of the learning experience when they are active and provide views, as opposed to long, stark, and linear places. Vistas into and out of learning spaces can be created without causing distraction. So much of students’ and teachers’ days are spent indoors that providing architectural and design elements that expand and open interior views and provide lines of sight can enhance cognitive activities. *13

The intertwining of technology into our lives has made physical space less associated with places of learning. In fact, technology offers new functionality to informal spaces, writes Dugdale. *14 Space is not assigned to a specific learning task or activity. “As a result,” Diana G. Oblinger, author and president and CEO of EDUCAUSE, writes, “the notion is emerging of the entire campus—not just classrooms—as a learning space.” *15

Students own the technology they bring to campus. No longer must they rely on hardware or software coming from static places (think of yesterday’s computer labs). And even if students aren’t toting laptops, campuses are filling multiple facilities with sophisticated equipment and software for student use. Wi-Fi and the Internet have changed the way we think about technology access and facilities.

Nondesignated spaces have educational value and contribute to “creating a sense of community,” according to Dugdale. *16 It’s true that shared places—libraries, cafeterias, student unions—are places that one associates with community. Connecting these community spaces with learning opportunities is what informal learning spaces are doing.

Design Problem

Learning will happen anywhere: from parking lots to classrooms to dormitory lobbies. If a conversation in a stairwell can become an opportunity for real learning, then institutions should take the lead in providing informal learning spaces where spontaneous, unscheduled learning opportunities abound. The challenge is to plan these spaces so well that the unplanned is always at home there, to create “socially catalytic spaces,” as George Kuh describes them in Student Success in College: Creating Conditions that Matter. These spaces must offer, but not dictate, learning opportunities. The challenge, says Whitmer, is to design opportunities for serendipity and unplanned activities into a space. And an added challenge, she notes, is to achieve these opportunities in existing buildings as well as new construction.

Solutions

The Herman Miller Education team, along with its sales and dealer partners, is collaborating on a number of campus-based, informal learning space research projects around the U.S. Our research consistently indicates statistically significant improvements in the amount of student-to-student and student-to-faculty engagement in these types of spaces. Excitement levels during group work increase. Students and faculty tend to extend their conversations outside of the classroom. And the opportunity for learning from each other—student or faculty—increases.

These results are evident in three universities that have created informal learning spaces with assistance from Herman Miller. In each case, the university’s design solution for the space represents a departure from its traditional approach to learning spaces. Each school operated under a different set of objectives and goals, and each has its own unique culture. And in each case, these schools have successfully created stimulating, flexible, and engaging places where there is much “hanging out” and a whole lot of learning taking place.

Xavier University, Cincinnati, Ohio

Xavier University’s strategic goal for the first decade of the 21st century is to transform teaching and learning on campus and become the nation’s leading comprehensive Catholic Jesuit university. The physical symbol of this transformation is the Learning Commons building in the Hoff Academic Quad that will open in 2010. Xavier is currently in the middle of a capital campaign to finance the Quad project—a somewhat unusual campaign in that it is only partially about bricks and mortar. “Our capital campaign is to enhance and revolutionize the student learning experience on campus,” says Bob Cotter, associate vice president for Information Resources. “The Learning Commons is simply the visible sign of what we mean by this campaign.” *17

Xavier’s Learning Commons will be a facility that supports new models of teaching and learning. It is a flexible environment with easy access to information resources, technological tools, and support services. In order to develop and test the new service models needed to support the activities in the Learning Commons, Xavier created three prototype spaces on the first floor of the McDonald Library. A collaborative learning zone, a faculty development center, and an integrated service desk comprise “test beds,” as Cotter refers to them, that are already facilitating new ways of learning, teaching, and working.

The Connector space at Ferris State University encompasses all of the attributes of great learning spaces. The Park (left) is filled with the varied landscape of Resolve furniture. The mobile tables and chairs support the changing activities of the faculty and students. The Town Hall space (right) provides an engaging environment for presentations and scheduled learning.

The collaborative learning zone is a highly mobile and flexible space. The product selections Xavier made needed to complement and support those characteristics. Resolve workstations dot the area and are the only furnishings in the space that students can’t move. Yet the workstations give students flexibility to work individually or in pairs, and the design and color scheme add visual interest and vitality. Mobile chairs and Bretford mobile tables give students an easy way to adapt the space to varying uses and varying numbers of students. Relaxed study spaces are created with Intersect portfolio Kotatsu tables and a variety of soft seating. Intersect portfolio display products give students and faculty tools for brainstorming or visual problem solving.

The intent in the design and furnishings of the collaborative learning zone was to provide students with options for individual and group work and to support a variety of activities, from concentration to relaxation. “Our goal with this prototype space is to have students tell us what they like and don’t like about the space and the furnishings,” says Cotter. “Students ‘own’ this space. It’s intuitive and mobile. How it looks at 4 p.m. will be different than what it looks like at 1 a.m.”

Cotter continues: “We’re able to observe how it gets used. How is the furniture moved around? Which areas see more use? This feedback will inform the changes we make. If we approach this coherently, we’ll be rebuilding the commons every year.” Cotter considers this a good thing. Continuous planning for the unplanned activities within the collaborative learning zone is a welcome expectation.

Greater discourse and interaction among faculty members is critical to Xavier’s goals. The Center for Teaching Excellence provides formal and informal spaces for peer collaboration. A mix of tables that meet conference needs as well as smaller consultations and lounge and soft seating create a working faculty lounge space. “We are drawing faculty from different colleges (Arts and Sciences, College of Business, and College of Social Sciences, Health and Education) and giving them space to casually interact in ways they haven’t been able to before,” says Cotter.

The arrangement of this space is providing more opportunity for informal and serendipitous encounters between faculty and students. Faculty appreciate the activity and social engagement of the informal learning space. Students see faculty in a more casual setting. Public spaces blend generations, activities, and purposes. The collaborative learning space at Xavier does that, as well.

“The biggest experiment of all in this prototype space is the integrated services desk,” says Cotter. Big because it merges cultures and departments under one group called Discovery Services, which Cotter is leading. And big because it will become the “nerve center” of the learning commons, providing a one-stop student and faculty service experience. Yet this is a necessary element in creating successful informal learning spaces. IT support and reference support are important services to blend into a space in which students are using computers and other multimedia equipment, and searching the Web or reference collection for help with a project.

The space has been in operation since January of 2008. After nearly six months, what has Cotter learned from the prototype? “Instead of designing a picture perfect set-up, we need to continue to inject more flexibility in terms of the students’ use of the space and the furnishings. We can’t fall into designing the space to conform to technology or prescribed uses. We have to keep meeting students where they are—design can’t be hardwired.”

Ferris State University, Big Rapids, Michigan

Roxanne Cullen is a professor of English at Ferris State University and instrumental in the development and design of the school’s Interdisciplinary Resource Center. The renovation project took an existing space, called the Instructional Resource Center, and transformed it into the Interdisciplinary Resource Center. While the initials of the space remain the same, that’s the only thing. Moving from instructional thinking to interdisciplinary thinking represented a significant shift. “This was a transformation of ideas, of the mission of the school,” says Cullen. “We cannot change the idea of a university without considering the physical presence; likewise, we cannot change the physical presence without vigilant attention to the idea of the university.” *18

The Connector space within the IRC exemplifies the blending of the physical and the idea. A large and open space—50 feet by 200 feet, with 30-foot-high ceilings—it connects two traditional classroom facilities. It was intended to become a city park of sorts, a public space where students, faculty, and staff could come and touch down for a short or long time. The design and furnishings of the space provide places where all types of informal learning take place.

Spaces that provide opportunities for student-faculty engagement are key to informal learning. Herman Miller’s My Studio Environments creates great spaces for collaboration and student-faculty interactions.

Main Street, defined by a tiled walkway, runs through the entire space. To keep the City Center, along one side of the walkway, open and airy the university filled it with Resolve infrastructure. The infrastructure’s overhead trusses carry the power and data, but everything else in the space is mobile. Interspersed throughout the City Center are freestanding Bretford tables (both standing and seated height), Intersect portfolio display products, Caper chairs, and Celeste lounge seating. Screens—that are part of the Resolve infrastructure—are printed with cloud images, brightening the space and further bringing the outdoors in. Windows run the length of each side of the Connector space.

On the other side of Main Street is the Park, a space filled with movable Intersect portfolio tables and lounge seating. Students and faculty sit under trees, surrounded by greenery. In one corner of the Connector is the Town Hall, separated from the City Center and Park by Intersect portfolio white boards, creating a semi-enclosed space that is used for multimedia presentations, meetings, and formal, scheduled group work.

The Herman Miller products that fill the space contribute to the overall ambiance and visual message of the Connector area. Bright and airy, the products, along with the architecture, bring the outdoors in. The cloud images and curved lines of Resolve components complement the views along the windowed corridor. Ease of change and flexibility are supported with mobile seating and tables. Study groups can shrink or expand, and the furniture follows suit. Display products are also mobile and can be moved wherever needed.

As with Xavier’s informal learning space, the Connector space brings faculty and students together more regularly and informally. The faculty center offices are located in the IRC, so the Connector space brings all disciplines together. Faculty from all around campus teach and work in this space, so visibility of faculty to each other and students to faculty is enhanced.

“The design of the Connector space recognizes that learning takes place outside the classroom,” says Cullen, “which is important, since the space connects two formal classroom facilities.” *19 In writing about the Connector, Cullen and Harris note it is the “designed spill-out space for students to work beyond the confines of the classroom.” *20

Ohio State University Digital Union, Columbus, Ohio

Xavier’s and Ferris’ informal learning spaces are relative newcomers to their campuses. The Digital Union, at Ohio State University, has been in existence since 2004. Its history confirms what is widely recognized: Informal learning spaces provide students with the kind of environments they prefer to spend time in. The Digital Union’s 2007 annual report counts 12,000 visits during the academic year, two-and-a-half times the number of students who visited the previous year. Unique users grew by nearly 250 percent. *21 To meet the growing demand, the Digital Union will expand from its current 2,000 square feet to 13,000 square feet. *22

The Digital Union is part of the science and engineering library, but its services are open to all OSU students. Its mission is to provide a “low-risk trial-and-error experience with technology, leading to informed decision-making.” *23

“The space was created to give students access to the latest and greatest computers, equipment, and software,” says Victoria Getis, director of the Digital Union, “the complex and sophisticated tools that students don’t typically have at their disposal.” “Digital media is becoming a primary tool for research and projects,” says Getis, “so the need for this access is growing.”

The Digital Union needed to reflect innovative and forward thinking in its design, as well. The space is filled with Resolve products. They represented a completely different look and handled technology well, essential for such a technology-intensive space. Resolve’s progressive design also brings visual excitement and activity to the Union.

In the years since it opened, the Digital Union has continued to be a highly interactive place. Interactivity is enhanced not only through the digital equipment and activities in the space, but also by the highly mobile and adaptable furnishings throughout it. Bretford tables and Caper and Mirra chairs offer students a means to easily reconfigure study areas to meet immediate needs. Eames molded plywood chairs and lounge furnishings also provide students with more relaxed study and collaborative areas.

A recent product addition to the space is a number of My Studio Environments offices for both staff and student work areas. “It represents the latest and greatest offering today, and it supports the multiuse needs of our space,” observes Getis. “Beyond office space for staff members, My Studio works well for consultation purposes, too.”

The blend of informal learning and technology support/education is the daily mix at the Digital Union. Students typically come to access media tools, but increasingly they also come to study in a relaxed and stimulating environment. That wasn’t always the case, according to Getis. “When the Digital Union opened, it was a ‘by appointment only’ place. If students weren’t there for an academic, multimedia task, they were asked to leave. That’s hard to imagine now, but at one time it was pretty unwelcoming. It didn’t take long for that to change.” This shift underscores how attitudes about the value of informal learning spaces have changed, even over a few years.

It also points to the significant role students have played, and continue to play, in shaping the facilities and the design of campuses. One lesson Getis has earned since the Digital Union opened is that the space has to be adaptable to the needs and uses of OSU students.

Getis has watched the informal learning and peer mentoring that occurs among students at the Digital Union. “Students regularly help each other in a casual way, just leaning over to the next table and asking a question. This peer mentoring happens all the time.” It certainly underscores the value of informal learning spaces within a university environment and their influence on developing life-long learning—and transferable skills. Getis provides a case in point: “I was observing a student who was particularly good at helping other students. I wandered over and asked if she had a job. She had been working for the OSU transportation department, but now she works for us.”

Summary

Informal learning spaces do not belong to any one department or school within the university. They belong to the campus community. As multiuse, flexible, and undesignated places, shared spaces make a positive economic case for space use.

The transformation Ferris State University realized in its IRC wasn’t only about how the space was created, but also about how the school would maximize the use of the space after the transformation. *24

Herman Miller’s Whitmer agrees: “Unlike a hallway of empty classrooms that are used by one department sporadically throughout the day, informal learning spaces are in use and occupied during all hours of operation, often on a 24/7 basis. Undesignated and unscheduled spaces, in and of themselves, are more resourceful.”

Company Informations:

Le Office Furniture Manufacturer

www.letbackrest.com

Address: No.12, Nanhua Road, LongJiang ,Shunde,Foshan, Guangdong, China (Mainland)

Email: sale@letbackrest.com

skype: kinmai2008